Hotspot Cities Symposium Draws Global Leaders to Discuss Conflicts Between Urban Growth and Biodiversity

In June, during the lead-up to Design With Nature Now, the conference that marked the launch of the Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology, Weller hosted dozens of planners, conservationists, and policymakers for a two-day symposium at Perry World House. The object of their queries was stark.

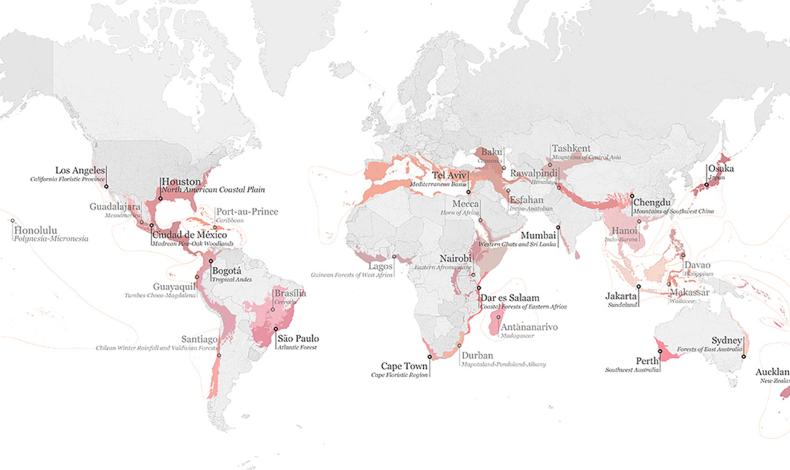

At the edges of cities and metro regions across the world—the peri-urban landscapes where developed land and rural land overlap—human settlements are pushing up against sensitive plant and animal habitats and threatening to accelerate the already swift decline of biodiversity on earth. Such conflicts are common. But in some cities, where growth is encroaching on ecosystems rich with unique species, called biodiversity hotspots, the threat is particularly acute. Those are the places that Richard Weller, the Martin and Margy Meyerson Chair of Urbanism and professor and chair of landscape architecture at the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design, has identified as "hotspot cities." In June, during the lead-up to Design With Nature Now, the conference that marked the launch of the Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology, Weller hosted dozens of planners, conservationists, and policymakers for a two-day symposium at Perry World House. The object of their queries was stark.

“Life on earth is dying,” Weller says, “and we’re just not meeting the challenge.”

Attendees came by invitation, from Auckland, Osaka, Los Angeles, Cape Town, Mumbai, and Mexico City, among many others. They represented institutions like UNHabitat, the Regional Plan Association, The Nature Conservancy, ICLEI, and Google. They were landscape architects, architects, scientists, scholars, and government officials. They presented scientific research, environmental studies, policy questions and political problems.

“There’s a lot of good will and there’s a lot of grassroots projects,” Weller says. “And there’s concern that there is a lack of global continuity and communication between the cities that are experiencing this problem.”

At Penn this spring, Weller and David Gouverneur, Associate Professor of Practice in the Department of Landscape Architecture, led a studio that took Bogotá, Colombia, as a case-study hotspot city. Working with local officials, students created a large-scale plan to restore the Bogotá river and inject the metroregion with green space. One official, Juan Camilo González, an aide to Bogotá Mayor Enrique Peñalosa, attended the Hotspot Cities Symposium to discuss a large-scale housing development project that has sought to protect and connect existing habitats through an innovative funding strategy that puts the financial responsibility for the public and ecological investments on developers. Other speakers presented work related to managing habitat along the Central Flyway bird migration route near Houston, documenting distinct urban landscape typologies in Los Angeles, and protecting orchids in Perth, Australia.

Zuzanna Drozdz, the Research Coordinator for the Hotspot Cities Project taking a year off from her Master’s in Landscape Architecture at Penn, reviewed a white paper compiling research on planning policies and design initiatives in each of the 33 Hotspot Cities. It was an attempt to measure each city’s degree of consciousness about biodiversity by looking at everything from planning policies to cultural connections to nature. A draft of the paper was presented as background research to the participants prior to the symposium, and will be hosted on the web in a form that can be edited by participants in different cities.

The challenges facing each city in managing its growth are layered. Even when some governments are willing to adopt best practices, jurisdictions are often fractured, with no clear authority charged with planning at the scale of a bioregion. Political cycles complicate efforts to control growth across time. Informal settlements spread out in metro regions to meet immediate needs that are unmet by formal development. Formal policies contribute to low-density sprawl. Important land for biodiversity is held in private hands. The public may not value critical land if it’s perceived to be even marginally degraded. Economic crises take attention away from environmental concerns. Environmental agendas themselves — from clean water and air initiatives to fossil fuel divestment — may overlap but not perfectly align. So a question underpinned the whole symposium: Could the participants form some sort of global alliance that would aid each city in adopting planning practices that mitigate damage and protect critical habitats?

Marshaling the will and resources to protect those habitats would require a range of tactics, the participants agreed during a roundtable discussion that capped off the symposium. A global alliance — something akin to the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group — could serve that goal by unifying efforts under a single brand, attracting financial resources, and helping to enforce planning initiatives over time and across different jurisdictions. Other ideas included establishing new student exchange programs, or directing existing ones to focus on biodiversity. No formal organizations have been incorporated yet,but Weller says the symposium laid important groundwork for potential solutions.

“There is a need for some sort of globally coordinated network of cities that help one another with knowledge-sharing and political clout and economic attractability,” Weller says. “It’s a really critical issue, and the structures that exist are not powerful enough to deal with the issue in a way that is commensurate with the scale of the problem.”