Monument Lab Celebrates ‘Report to The City’

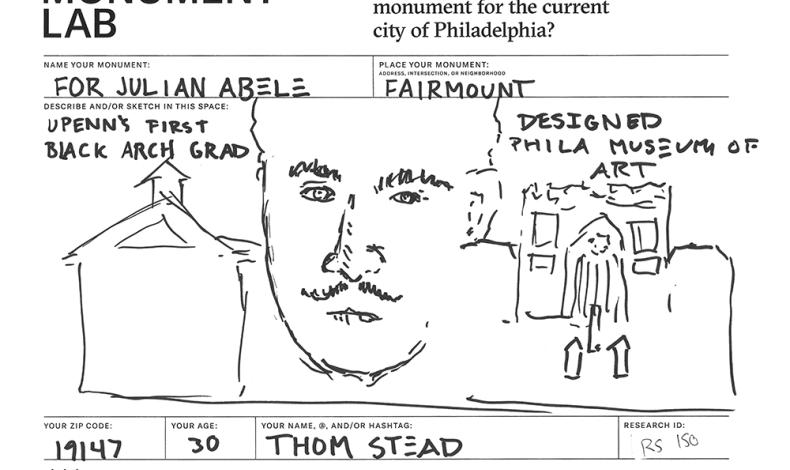

The question was straightforward enough: “What is an appropriate monument for the current city of Philadelphia?”

The question was straightforward enough: “What is an appropriate monument for the current city of Philadelphia?”

But the answers, projected on a screen last week at the release party for Monument Lab’s Report to the City, reflected a dizzying variety of ideas for reimagining the symbolic landscape of Philadelphia. We could replace William Penn on top of City Hall with a statue of Marcus Garvey. We could plant a statue of Octavius Catto face-to-face with Frank Rizzo across from City Hall. We could erect a clenched fist in Malcolm X. Park. We could build a monument to Fannie Jackson Coppin in front of a Philadelphia public school building. What couldn’t we do?

“One of our goals before the exhibition was, can we invite the public to unfreeze the monuments?” said Paul Farber, a lecturer in the Department of Fine Arts at PennDesign and the artistic director for Monument Lab, a years-in-the-making public art project that culminated last summer with a series of installations around Philadelphia. “To understand that they are products of previous eras—that although they give off the idea they're permanent, they're always part of politics in a moment? And then last summer, after the tragedy in Charlottesville and the movement swelling around the country, here in Philadelphia, people were ready. They were unfrozen from day one.”

At the release party, held at Slought on Penn’s campus, the reports, published on broadsheet newsprint, were piled in stacks around the room. The next day, Monument Lab was planning to distribute them around the city. The report is also available online, as are all 4,500 submissions from Philadelphians. The Monument Lab team—including Farber, PennDesign Professor and Chair of Fine Arts and Monument Lab Chief Curatorial Advisor Ken Lum, and Director of Research Laurie Allin—had presented the report to city officials days before. Philadelphia poet Ursula Rucker performed excerpts from her epic poem “Ode to Philly.”

Farber said that when the team began working on Monument Lab in 2012, it was careful not to present the work as something new: Artists, activists, and students had already been talking about the ways that public monuments fail to reflect the depth of American history for years. As the project moved toward the installation phase last summer, it coincided with a wider acknowledgement of that limitation, and became “a profound cultural moment,” Farber said. Nobody had asked for there to be a report, he said. But it felt like the right way to respect the contributions of the city’s residents was to turn them into something permanent.

“We want to make sure that this work has value, and we want to make sure that it's accessible,” Farber said. “And so there's a number of ways people can interact with it--they can download the dataset, they can search the proposals, they'll be able to visit the archive at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries. But we wanted a report that could fit in your hands, just like a blank piece of paper that we used as our research interface, to make sure you could hold this and give it serious thought.”