Excavating History in Designing “Mixing Chambers” for the Penn Museum

Students entering architecture school often think of design as linear, says architect Vanessa Keith (MArch’00), who joined the faculty in the Department of Architecture this fall.

Students entering architecture school often think of design as linear, says architect Vanessa Keith (MArch’00), who joined the faculty in the Department of Architecture this fall. They tend to want to move forward in stages: first the floor plan, then the elevation, and so on. But “creativity doesn’t work that way,” says Keith, who is principal at Studioteka in Brooklyn. This reality is reflected in the way the first-year graduate architecture studios at the Weitzman School are organized, so students become nimble at moving between perspectives and scales, and thinking through the ethical and political implications of their work.

“If you’re constantly changing the way that you’re looking at a thing, then as you’re changing the way that you’re looking at it, you’re learning, and you’re also progressing in your ability to do design,” Keith says. “And I think it’s really important that design be beautiful but also meaningful.”

Keith taught one of six sections of the Architecture 501 studio, in which students designed new spaces for the Penn Museum in the context of wider conversations about systemic racism and decolonization in cultural institutions. As the syllabus notes, the Penn Museum is among “many monuments and museums [that] were built a century or more ago by people who took colonialism, racial hierarchy, and slavery for granted.”

It’s the second consecutive year that students engaged intensively with the Museum’s collections, through a partnership initiated by Associate Professor of Architecture Andrew Saunders, who directs the MArch program, and Anne Tiballi, Mellon Director of Academic Engagement at the Museum. The studios last year were organized under the banner of “Curious Cabinets,” in reference to the colonialist concept of the cabinet of curiosities. This year’s studios took on the theme of Mixing Chambers, “enclosed spaces intended to foster the combination of two or more discrete elements.”

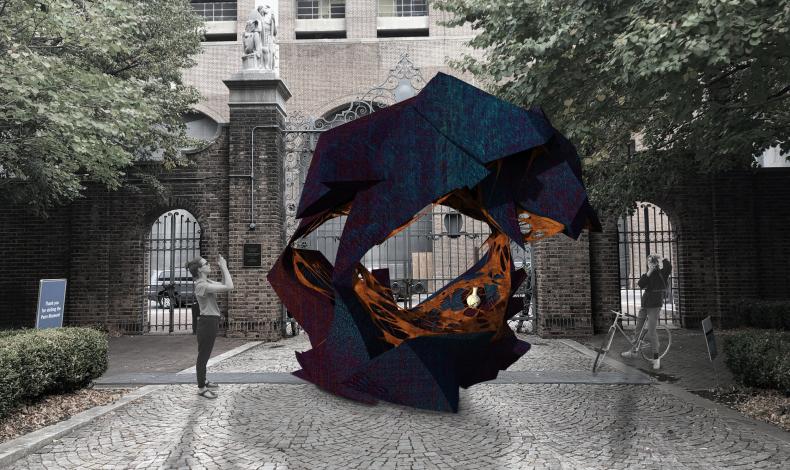

As part of the studio, students worked on three projects. In the first, they each chose an artifact from the Museum’s American Section—which includes items like dolls, jars, baskets, bowls, boxes, whistles, and pipes crafted by North and South American indigenous culture—and designed a container to hold and display the object. The second project had students, in teams of four, design and fabricate “mixing chambers” housing all four of the artifacts they selected. The results of that project were displayed during midterm presentations as a public exhibition in the Penn Museum courtyard. Finally, each student designed an Archive and Research Extension for the Penn Museum American Section, envisioned in the syllabus as “a new public gateway or threshold to the museum” facing the courtyard.

Keith says the assignments were organized to let students work at different scales while maintaining a certain continuity of purpose throughout the semester.

“If you do three completely different projects over the course of a semester, it’s exhausting and overwhelming, whereas with this one, they were able to sort of build on an idea and go up in scale,” Keith says. “And then at the end of the semester, they’re working at the largest scale, and they’re also working independently for the first time.”

Each of the six studio instructors had an original interpretation of the “mixing chambers” concept. For Keith, who studied religion and non-western philosophy at Columbia as an undergraduate, the studio was organized around “Chaos and Cosmos.” She aimed to push students to “explore the relationship between the artifact as simultaneously precious physical construction and scanned digital simulacrum, as well as its deeper connection to ancient and contemporary systems of meaning.”

Keith asked her students to create a “DNA strand” based on their artifact containers, which they then combined with their teammates’ strands during the middle portion of the semester to create the mixing chambers to be displayed in the Museum courtyard. She also asked them to select a legend or creation myth from the culture where their artifacts originated, and to research the histories of the site—from indigenous languages spoken in the area to historic environmental features like underground streams and creeks—and incorporate those elements into the design. The goal was to have students combine the physical qualities of their artifacts with the cultural histories of their origins and the constraints and characteristics of the museum site to create a design that told a story.

Jesse Allen, an MArch student who studied economics and environmental science as an undergraduate, said he wasn’t sure what to expect from his first graduate architecture studio, and that he tried to keep an open mind about learning new processes. Working in a team with students Jenna Selati, Leah Janover, and Xinlei Liu Allen designed Hollow Hierophany, reimagining the cave from the Caddo Nation’s creation story “to reinforce the active present and future of the artifacts and their originating cultures.”

“It was interesting to see what each group member saw as ‘essential’ at each step, whether in determining their own artifacts’ DNA or what aspects of other DNA strands they incorporated or emphasized in each iteration,” Allen says. “Finding this key aspect or aspects of an artifact or design was challenging, and I thought our group worked well to resolve some of the confusion to achieve a meaningful design.”

Keith organized a workshop for students in WebVR, a platform that allows designers to build work in a virtual environment and experience it from different angles, above, below, and within their designs. The platform also allows students to share work with each other and with anyone else who has a phone or computer. And it’s a preferred tool of many of the artists and designers that students studied and worked with in the course, including many indigenous futurist artists. Throughout the semester, Keith pushed students to continuously review their work from different perspectives and at different scales, and to incorporate more information about the cultures that produced their artifacts.

“One of the things that’s important is to keep bringing in another element to sort of weave back in,” Keith says.

Keith says the constraints of COVID-19 learning also opened up possibilities the group might not have considered before. The students used collaborative tools like Bluescape and Discord to work with each other and with the artists Olivia McGilchrist and Tom Watson, also known as Commonolithic, who helped the students learn how to use WebVR.

For their final projects, Keith’s students selected nonprofit organizations to partner with on the design of the Museum extensions, including the Initiative for Indigenous Futures, a platform for imagining the future of Aboriginal communities in Canada; the Caddo Conference Organization, which promotes archeological knowledge of the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma; and the Philadelphia Archaeological Forum, which works to protect and preserve the archeological heritage of the city. By the time they completed the semester, students had employed a range of design approaches and presentation media, including virtual and augmented reality elements. And they entered into a critical conversation about the role of cultural institutions in creating and perpetuating injustices in society.

“We need to change the planet, we need to live in a more sensitive way, and we need to respect each other more,” Keith says. “So I think that a project like this is really important, especially for beginning students of architecture to then take forward into their lives as designers.”