When Three Schools, and Three Countries, Converge in One Studio

The pandemic meant that studio travel wasn’t possible. Over the course of the fall semester, students worked together to study three different sites in Caracas, Guadalajara, and Bogotá.

In most years, the students in David Gouverneur’s Urban Design Studio would spend a semester learning about a single place, making connections with local students, faculty, and leaders, traveling to the sites. The pandemic meant that studio travel wasn’t possible. But instead of scaling back, for the Fall 2020 Semester, Gouverneur tapped into a network of collaborators to expand it.

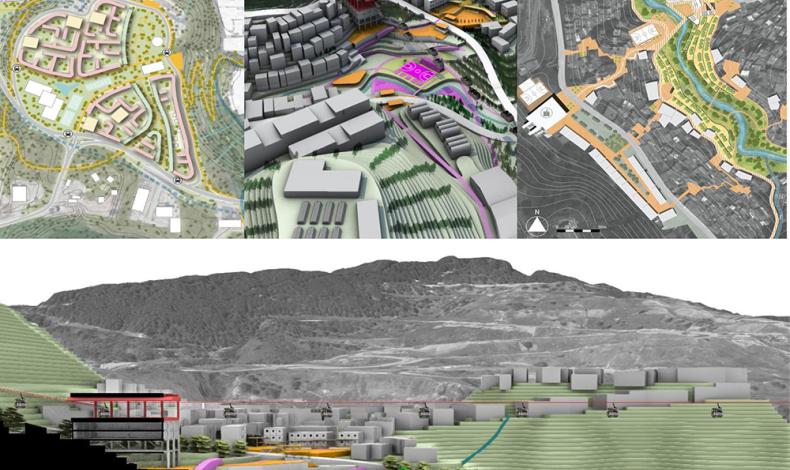

Over the course of the fall semester, students at three different universities—the Weitzman School of Design, The School of Architecture at La Universidad de Guadalajara in Mexico, and the Architecture Program at Universidad Simón Bolívar in Venezuela—worked together to study three different sites in Caracas, Guadalajara, and Bogotá. The three sites are comprised predominantly of informal neighborhoods; all at the fringe of environmentally protected and agricultural zones, but are very different in terms topographic conditions, scale, degree of consolidation, and in relation with formal and higher-income areas. (The students' presentations are available to watch on video: Caracas; Mosquera; Guadalajara.)

“It was maybe the most complex studio I’ve ever run in 40 years of teaching,” says Gouverneur, an Associate Professor of Practice in the departments of Landscape Architecture and City and Regional Planning. “We did not know if the online international experiment was going to work, and then it turned out to be outstanding.”

The studio is built around the concept of “informal armatures,” which Gouverneur, author of the 2018 book Planning and Design for Future Informal Settlements: Shaping the Self-Constructed City (Routledge, 2018), has been developing for decades. Students focus on ways to support and improve existing communities built by people, as well as to assist the growth of new ones. The approach involves supplementing the settlements with the urban conditions that, says Gouverneur, residents achieve on their own, such as the protection of the environmental assets, public spaces, community services, infrastructure and lots for new self-constructed dwellings. New housing is provided to relocate families from high-risk sites.

For the first three weeks of the semester, students took in lectures and virtual site visits, and three teams composed of students from each of the schools worked together to research the history, natural systems, urban systems, cultural landscapes, and socio-economic conditions of the courtiers, regions, cities and sites. In the process, the students encountered the views of students of different academic and cultural backgrounds, some with a deeper knowledge of the sites, others engaging them from afar and delving into unfamiliar conditions and topics. Then, they took part in collaborative weeklong charrettes, presenting their findings to faculty from the three universities and other international guests in virtual meetings. This set the stage for the continued work in the studios at all three universities, which took different approaches. Students gave midterm and final presentations first at their home university, and then they came together to compare the results from other teams and individuals that were focused on the same sites.

“This incredible collaborative effort would not have occurred if we were not forced to creatively work online,” Gouverneur says. “And it would have been just impossible without the new Zoom society we have,” says Diego Bermúdez (LARP’16), a graduate of the Department of Landscape Architecture now residing in Bogotá who selected the Bogotá site for the studio. Bermúdez, a principal and partner at Bermúdez Arquitectos in Bogotá, has been studying La Sabana de Bogotá as a fellow with the Landscape Architecture Foundation. For the studio, he selected an area of Mosquera, a city Municipality adjacent to the capital city that includes a network of irrigation and flood-control canals, which has been seeing a lot of suburban development.

The students’ challenge was to look at ways that formal and informal development in the area could be made more ecologically sensitive, and improving agricultural production. “My interest is not only about how this area is going to be urbanized in the future but about how the irrigation district is going to evolve over time,” Bermúdez says. “The main issue here is if we keep urbanizing this place without actually protecting the system of canals, we will most likely end up with an impervious area that will flood in the future.”

Students from different schools studied the three sites from different angles. Weitzman students say that their wide-angle approach at the beginning of the semester was complemented by some of the more granular experience of students who were living in Latin America. Each team relied on one or two people who could communicate in English and Spanish to share perspectives on site analysis and planning, says Palak Agarwal, a student in Weitzman’s Master of Landscape Architecture and Master of Urban Spatial Analytics programs who worked on the Bogotá site. (The studio was open to Weitzman students in the departments of Landscape Architecture, City and Regional Planning, Architecture, and the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation.) While it was sometimes challenging to communicate, Agarwal says, the perspective of Latin American students enriched the studio. And while it made it possible to come together frequently, communicating remotely also had its drawbacks. “Even though I might think I know the culture of Bogotá, it’s a different thing being there and experiencing it firsthand,” Agarwal says.

Software programs like Google Earth and ArcGIS are powerful tools to help understand a place, says Vincent Ferriola, a second-year Master of City Planning student who worked on the Venezuela site. But those tools can also reinforce a limited, “top-down” perspective that has haunted the history of city planning, they say. That’s why, without the ability to visit a site and build relationships with residents and local leaders, it was beneficial to work with students from a variety of backgrounds, Ferriola says. “We all see everything slightly differently, and I think ultimately that’s a healthy cohesion—to have all these perspectives come together,” they say.

Instructors did their best to provide a simulation of site visits. Bermúdez says that in landscape architecture, it’s important to experience the various qualities of a place—the smell, the weather, the moisture in the air—and that was something that he wasn’t able to convey through the video tour he gave to students. But at the same time, the concentrated focus on remote learning allowed students to take software and other technology as far as they can go.

“We are shaping the ways landscape architects and architects are going to be learning from places in the future, most likely,” Bermúdez says. “And I think [artificial intelligence] and remote sensing and even security cameras are going to be, at some point, accessible to all, and we’re going to be able to actually understand places from a distance more easily with every year that passes.”

For Gouverneur, it was a chance to reconnect with his undergraduate alma mater, Universidad Simón Bolívar, where he taught 25 years in their Architecture and City Planning programs, and the first time in a decade he’s been able to lead a studio in his native Venezuela due to the political and economic crises which has impeded fieldtrips to the country. Previous iterations of the Urban Design Studio have focused on sites in Ciudad de Guatemala, San Juan de Puerto Rico, San José de Costa Rica, Cartagena, and Bogotá.

After years of leading studios focused on informal settlements, Gouverneur believes scholars and practitioners have begun to realize that ignoring these communities—which in many developing countries already are the dominant form of urbanization—is an act of neglect that will exacerbate social tensions and affect political stability and economic performance. But it’s still difficult, he says, to get a critical mass of political leaders interested in the well-being of these self-constructed communities. Politicians are typically not prepared to invest the time and effort required to advance improvement plans, nor the fact that they require permanent community participation and oversight to reduces the margin for corruption. He hopes this generation of young planners and designers can help to change that. “If these young professionals, permeate the political system—if they become council members or if they become mayors—that’s probably when the real changes are going to come about.”

Gouverneur received support from the Department of City and Regional Planning to produce a publication about the outcomes of the students’ research and the partnerships formed to make the studio run. The publication, which is expected to be complete in the spring, will likely have online and print components, Gouverneur says, highlighting the “interdisciplinary, transcultural” approach of the studio and the opportunities in online, international exchange.

Gouverneur’s work in Latin America will continue in the Spring 2021 Semester. His students will turn to sites in Quito, Ecuador, in collaboration with faculty and students at La Pontifica Universidad Católica del Ecuador. Gouverneur tapped his local networks and received support from Eugenie Birch, Nussdorf Professor at Weitzman and co-director of the Penn Institute for Urban Research, and Weitzman Dean Fritz Steiner to establish an agreement of cooperation with the Secretariat of Territorial Planning, Habitat and Housing of the Municipality of Quito. The Municipality has selected three diverse sites as pilot projects, and will furnish or facilitate valuable research in the form of base-maps, drone flights, virtual site visits, and community meetings over the coming months.

Editor’s note: David Gouverneur expresses gratitude to Professors Franco Micucci and Silvia Soonets from Universidad Simón Bolívar in Caracas, Venezuela; Ramón Reyes and Eliazar Reyes from La Universidad de Guadalajara, México; and Diego Bermúdez from Bermudez Arquitectos, Bogotá, Colombia; and their teaching assistants for their generous academic contributions. He also acknowledges Weitzman Teaching Assistants Francisco Ospina and Jeff Alexander and faculty members Franca Trubiano, Miriam García, Oscar Grauer for their valuable feedback. Gouverneur dedicated this studio to the late Lindsay Falck, a longtime member of the faculty at Weitzman who passed away in early 2020 who Gouverneur called “a pioneer in the appreciation and the attention of the self-constructed city.”